But Seriously ...

Licensed For Life

A cop who's seen it all reaches teens by lowering their guard.

By Zak Mucha

Originally published in The Chicago Reader, June 11, 1999

"When a drunk gets stopped by a cop, what does he try to convince the cop?" Mike McNamara pauses, eyeing the driver's ed class at Bremen High School that will be his audience for the next hour. The students are silent, thinking the commonsense answer can't be correct. "Yeah—that he's not drunk."

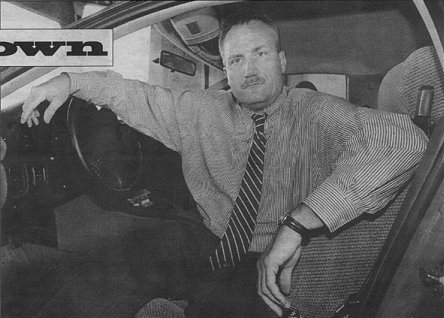

McNamara might not tell you he's a cop unless you're under arrest, but he shouldn't have to—an 18-year veteran and Park Forest detective sergeant, he may as well have C-O-P tattooed across his forehead. He might not tell you that he has a master's degree in criminal justice, that he graduated from the FBI National Academy in 1994, or that he's a four-time gold medalist in the World Police and Fire Games. But he will tell you more than you want to know about drunk drivers. One man poked himself in the eye while trying to pass the street sobriety test and immediately threatened to sue. Another vomited on McNamara's new shoes and then asked, "Is there a problem, officer?" Yet another man crashed into his neighbor's car and hid inside his own house; when McNamara and his partner came to the door, the man's wife answered while her husband stood naked in the living room. "It couldn't have been me, officer," the man protested. "I couldn't have been outside like this."

For 12 years McNamara has been teaching DUI prevention at his local high school, and in 1997 he helped found Licensed for Life, a nonprofit organization that teaches kids the implications of drunk driving, be they legal, physical, or moral. The program is funded by individual and corporate donations; McNamara and 12 other officers from the Park Forest, Chicago, and state police departments draw salaries for their work, but the program is offered to schools free of charge. So far it's sent speakers to over 250 Illinois schools, as well as to basketball camps, prisons, Rotary clubs, and teaching seminars. The organizers hope to make the program available across the state.

"Make them laugh and leave them sober" is McNamara's motto, and it works. For most of the hour at Bremen he has the class laughing. Suppose he saw Direese, a girl in the front row, at parties on two consecutive weekends, and both times she was obviously drunk. Now on the following weekend he sees her driving. "Say I'm doing radar," McNamara suggests, "looking for burglars, fighting crime. My squad's parked in the Dunkin' Donuts parking lot …"

Someone giggles at this, and McNamara's voice tightens. "What are you laughing at?" He polls the class, asking whether they think cops hang out at doughnut shops all day. After most of them raise their hands he begins a lecture on police stereotypes, pulling out a Dunkin' Donuts napkin to clean his glasses.

Then it's back to Direese's probable cause. "If she was drunk last Friday and she was drunk two Fridays ago and it's Friday again, she's obviously gotta be drunk tonight, right? I should stop her, right?" The class agrees, but McNamara explains that even if he'd pulled her over and she were drunk, he'd have lost in court because he hadn't had probable cause to stop her. What constitutes probable cause? "Say I walk up to her and ask her for her driver's license and she gives me her Visa card."

"Maybe she couldn't see," someone suggests. McNamara reluctantly agrees. But suppose she smells like beer? "Maybe someone spilled it on her," several people yell. Suppose her eyes are bloodshot?

"She's got allergies!" the students shout. "She's tired!"

"She's high," a boy in the corner blurts out.

"Oh, that's real good, counselor," says McNamara. "‘My client wasn't drunk; she was high.'"

Suppose her speech is slurred? "She's got a speech problem!" The students find an excuse for every sign of intoxication McNamara can list.

"Here's what a woman did to me one time," he says. "Handed me her license and dropped it. Picked it up and dropped it. Picked it up, dropped it. Picked it up, dropped it. Finally she said, ‘Hell, you get it. I can't.'"

"She got arthritis!" a girl yells.

"OK," says McNamara. "You see why every reason I have why she might be drunk, you can legitimately come up with a reason why she's not?" While all these clues can indicate that Direese is driving drunk, a cop can't arrest her unless she fails the street sobriety test. "I have to prove not only that she's drunk but that she's physically impaired to drive a car. So step out of your car, please." McNamara motions to Direese. She looks at the hand he's politely holding out for her. "Get out of your car, please, ma'am." She doesn't get it. "Girlfriend!" McNamara yelps. "Get out of your car." She giggles and gets up from her desk.

The street sobriety test is the most popular part of McNamara's presentation. He runs Direese through the test, and she passes easily. Then he hands her a set of "Fatal Vision" goggles. They resemble a scuba mask, but the plastic lens is tinted and pebbled; it compromises the wearer's sight and coordination as much as a blood alcohol content of .12 percent. Feet and hands aren't where they appear to be, and the edges of the room are blurred, making it difficult to aim a handshake. The test not only shows the students how silly drunks look but demonstrates the extreme conditions under which some people will drive.

The students howl as the wearer fails the most basic tasks—standing on one foot, walking a straight line, touching his nose. McNamara asks the wearer to give him a high five, to catch a tennis ball. Finally the goggles are put away and the class calms down. "Is it funny to watch people do this?" asks McNamara. "Absolutely. It's hilarious. But the scary thing is that this is exactly how drunks walk, talk, and drive cars."

McNamara knows better than just to lecture kids. Preventing them from drinking may be nearly impossible, and teenagers often ignore talk of "bad life decisions." Alcohol-related accidents are the leading cause of death nationwide for people between the ages of 16 and 24, and in the past year more than $12 million was spent treating youth for alcohol-related injuries at Illinois trauma centers. But those statistics may seem too abstract. Teenagers generally consider themselves invincible.

"Here's a little-known rule," says McNamara. "If you are 21, I cannot ask you to take a Breathalyzer test unless I've already charged you with DUI. If you are under 21, it's the exact opposite. Say I stop Dave while he's on his way home, taking a shortcut through the football field. During a game." McNamara runs through several different scenarios, covering Breathalyzer tests, bond hearings, legal sobriety, zero tolerance, license revocation, drug tests, blood tests, and Miranda rights. He explains that someone can get arrested for DUI even while sitting in the backseat with his date, because the Illinois Supreme Court has ruled that a person has "physical control of a car" if he's anywhere inside it with the keys in his possession. The class groans.

Once he encountered a driver with a staggering .395 blood alcohol level. The man was sitting in his car, which was parked in the parking lot of a tavern with the engine running, and he was swooning in his seat. When McNamara knocked on the driver's window he got no response. "I open the door and the guy falls out. He had his seat belt on. So his butt was touching the seat and his head was on the ground. And I hear, ‘What's the problem, officer?'"

To get a fair blood-alcohol reading a policeman has to wait 20 minutes so that any alcohol in the driver's mouth can dissipate. "So I sat there, wrote up the tickets and the report while this guy is babbling on and on. He looks at me and goes, ‘You know, your honor, I got this store in Chicago, you know, and last year these two guys came in and shot and killed me.'" The driver's score was "a half drink short of being legally drunk for five people." But one woman topped even that, registering .40. She was in a minivan with her two toddlers.

None of the students really notices until it's too late, but McNamara has gotten serious. The stories of silly drunks have given way to autopsy reports. He holds up a photo of tangled metal that was once a Pontiac Grand Am and points out the passenger seat. "The guy who owned this car I knew for ten years, because he lived around the corner from my house. I watched this kid grow up." The young man got hammered with a friend, and knowing better than to drive drunk, he gave the keys to his friend—who was even drunker. "Those of you who did the goggles, he was drunker than that."

Only a few blocks from home, the driver nodded off. His foot depressed the accelerator, and the car hit a tree going 65 miles an hour. "The kid that was in the passenger seat got thrown headfirst into the tree, catapulted out of the car because he wasn't wearing a seat belt." He died, and the driver woke up in the hospital. "A few months after that he came over to the Park Forest police station on crutches, his leg broken in three places, wired together, pins, his left arm broken, his collarbone broken, cuts all over his face from the glass. Turned himself in to me. He was the driver and he was drunk and somebody died. He was charged with reckless homicide. He pled guilty last year, he was found guilty. And his lawyer did a good job and got him probation. So here's a young guy with a conviction on his record for homicide. The kid told his lawyer, ‘I don't want that. Go back to the judge and tell him I want to go to jail.' He killed his best friend, but he still got probation."

McNamara points out that if they do decide to drink, they have a responsibility to not drink and drive. It isn't a public service announcement, but by now his voice is lower. "When it's somebody I know, it becomes personal. My daughter almost got killed by a drunk driver. I saw a woman in a drunk-driving crash burst into flames. Out of 400 DUI's, I've been shot at three times, stabbed once, hit with a pipe once, hit with clubs, punched, kicked, slapped, and spit on so many times I don't even count them anymore."

McNamara asks the students to think about their friends, to think of a person they might see every day and then call on the phone at night. "‘Whattaya doing?'‘Nothing.' In spite of the fact that nothing is new and nothing is going on, in spite of the fact that you saw them all day, you still find enough to talk about for another hour or two. Now think about your mother waking you up that night and telling you that person just got killed by a drunk. Can you imagine what it's going to be like now because that person is gone? That mental image you have is all you got left. What are you going to want to do? Do you want to forgive this person? What do you want to do?"

"Kill him," the students reply.

"Absolutely," McNamara agrees and pauses. "Change the scenario one little way: as you wake up, your mom is standing there crying and your dad is standing next to your mom and he looks upset. It's one of those deep sleeps where you don't know what day it is, you don't know where you are. You wake up a little more and you realize that you're not in your bedroom, but you're in a hospital bed, and then you look up and there's a cop standing next to you and he's saying, ‘Hey, can I talk to you? Are you awake?' ‘Sure, what's the problem?' you say. And he tells you the stupid, ignorant drunk that didn't know when to stop drinking because they were having too good a time, that person that killed your loved one, was you."

McNamara asks his students to be careful and think about what they're doing. The students are silent for a moment and then applaud politely. "The response is usually one of two things," McNamara says after they've all filed out. "Either there's applause or dead silence. I like the silence better."