an excerpt from:

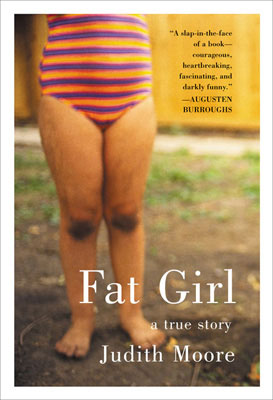

Fat Girl: A True Story

By Judith Moore

Fat Girl is a black diamond, revealing its hard brilliance only when you accept its invitation to descend into the soul of the loneliest little girl in the world. When you reach the center, the microscope becomes a wide-angle lens, suffusing your spirit with rage and mourning. Fat Girl is to-the-marrow honesty and monumental courage. It stuns, shocks, and saddens. It's the true blues ... because you know it's the truth. A magnificent achievement. —Andrew Vachss

Hudson Street Press, 2005 for online purchase |

And yet there's more to this. There is. I have a hard time telling about the two years that we lived in that apartment near Grant's Tomb, a hard time getting my finger on it. Truth was that Mama began to beat me on a regular basis. Beating me began to seem like part of a day's work. She chased me through the small rooms, the brown belt unfurling toward me like an infuriated snake. The belt lived a life of its own, its tip fiery on my bare legs. She screamed, "I am going to cut the blood out of you. I am going to teach you a lesson. I am going to break your will." There were times when the belt drew blood.

Early on I understood this business about breaking my will. Cowboy movies I'd see on Saturday afternoons showed scenes in which cowboys corralled and broke wild horses. The horses reared back their heads and snorted and whinnied. Their unshod hooves stirred dust clouds. The cowboys kept after them. So that no matter how heroic was the horse's resistance, there always came the terrible moment when the cowboy triumphed and the horse relinquished its will.

Sometimes the belt left welts. On those days, I wore knee socks to school. Even now that I am old, I feel Mama chase me from room to room, the brown leather belt flailing, its brass buckle closer and closer. I hear the buckle slash the air.

The shame that Mama's beating me compounded with the shame of my fatness left me cowering. I was nervous. I began to flinch, noticeably, at unexpected noises—backfires in the street, dog barks. If someone bumped me, I jumped.

By the time I got to fourth grade Mama and I didn't see much of each other. On weekdays, she rarely arrived home until dinner and she was gone Sunday, because she was the soprano soloist in a midtown church and she frequently sang both morning services and in afternoon chorales and oratorios. In Brooklyn and in Manhattan we did not eat our meals at the same table. In both boroughs, I ate in the kitchen. Mama took her plate into the living room and curled up in a chair and ate. She said she couldn't stand to watch me eat; it made her sick to her stomach.

Weekday afternoons I practiced piano lessons and played outside, but if Mama was gone, as she sometimes was, in the evenings, or on those Sundays, I felt lonesome and restless. I did not feel frightened. I was more afraid when she was home than when she was not home. When she was home every squeak of a kitchen cabinet door or swish of Kleenex pulled from its box was a scream.

I'd feel sick to my stomach after a real good beating. I felt shaky and frightened and weak and newly born into an uglier world than it had seemed before the beating started. The word lurid describes how I felt the world looked, lurid like bruises that are described as lurid. For Mama, the beatings seemed to clear the air, like lightning storms on Midwestern summer afternoons. After the beatings, I felt, well, "beaten." Real beaten.

I had to love someone who beat me. How did I manage this? I did love her and long to please her, but there was no pleasing her. She said that to me, about me, "There's no pleasing you." She said that I was ungrateful, she said, "Give you an inch, you take a mile." She said that I was "never satisfied." She said, "Don't you lie to me, Sister Sue."

I did lie to her. Every single day. I was not satisfied. I did want more.

My mother didn't love me and she did not tell me that she loved me. (I give her credit for that, for not saying, "I love you, darling. I do.") Grammy said she couldn't stand the ground I walked on and said so. My father forgot me. My mother kept saying that she was nothing but a doormat, that I treated her like my father treated her. "I," she would say, her eyes as wide as a dope addict's eyes, and she metes out this sentence slowly, each word louder than the other, "was nothing but a doormat for your father." By the time she gets to father, she is howling, and the "a" in father is a long, long howling a, the vowel of someone who has her leg caught in a trap.

Some time after I was ten and in the fifth grade, I began to make myself invisible to others. I skulked. I said to myself that I was a wallflower and I clung, therefore, to walls. I began more and more to hide myself from myself. I dug down further. I was tired of trying—to get and stay thin, to get along with Mama.

At school, I hadn't liked not being chosen for teams. I hadn't liked not being invited to birthday parties. I hadn't liked it that almost no one wanted to sit next to me at the lunch table. I hadn't liked that I almost always sat alone. But I got so I didn't care that much. I walled myself up, shut myself off. I found ways to amuse myself. I told lies that covered my grief. I said that my father died in the war. I said that my mother was going to be an opera star. I said I got Madame Alexander dolls for Christmas and a three-story doll house. I never mentioned Grammy. The lies were flimsy and didn't keep out the cold, but they were better than the truth. The truth was the same truth as always.

I began to chew my fingernails. I turned into a voracious eater whose meal was herself. I ripped and I tore at the flesh around my child nails; I licked, delicately and hungrily, at the blood that popped up in bright droplets at my chubby fingers' ends. I ate myself raw.

My cuticles became infected. My fingers were swollen. When I practiced the scales and arpeggios for piano lessons, when my fingers thumped out the simple pieces assigned a child, my fingers hurt. I did not care. I could not give up this chewing, biting, licking. I could not give up sucking at my own red blood.

I was not delicious. I was slightly salty. But I was my own breakfast, lunch, supper and snacks. I was eating myself, I see now, alive.

© 2005 Judith Moore. All rights reserved.

Click here to read "Why I Wrote Fat Girl" by Judith Moore.

Zero Pack: Judith Moore's Lily the Dachshund

"Moore Turned a Bitter Childhood Into Fiery, Honest Art"

(San Francisco Chronicle, June 20, 2006)