an excerpt from:

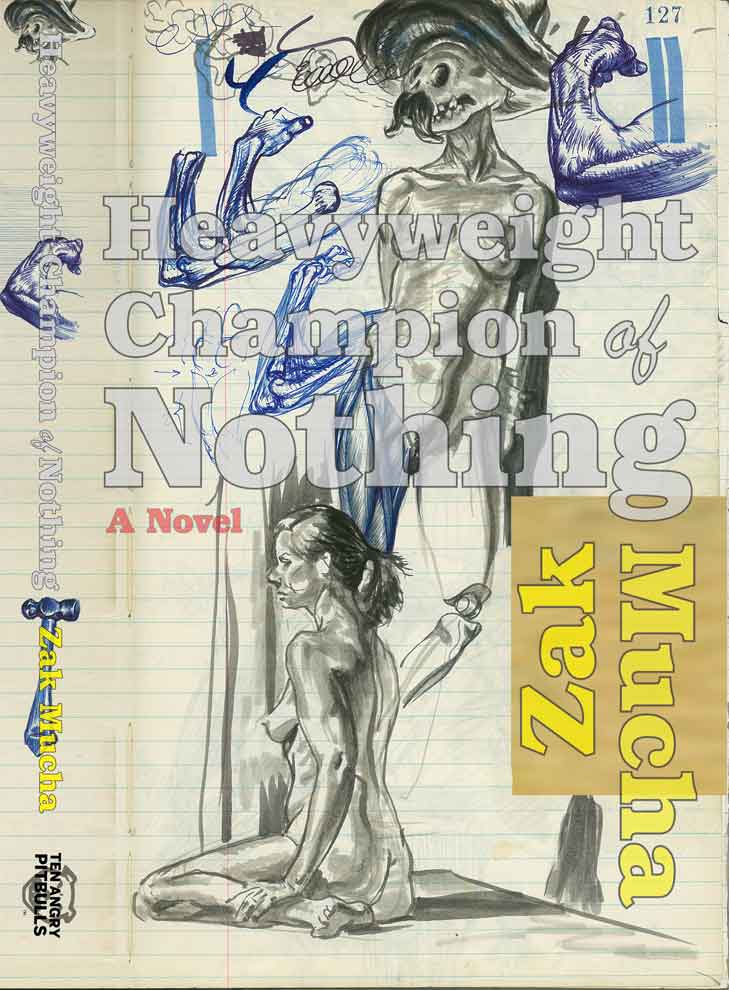

Heavyweight Champion of Nothing

By Zak Mucha

|

Onice cancelled our job an hour after we had all called in sick.

"Fucking prick," Paulie said. "Luke's already sitting with the truck up by his place."

"Onice going to pay us back?"

"No, he got off the phone real quick, said that was the cost of doing business — sometimes it's a wash. Didn't cost him anything, though. I told him he should have to pay his equal share for the truck rental and he fucking says we're not his employees — we're independent contractors. 'Like priests,' he says. Costs we 'accrue' are on our end, not his. He said if we wanted someone to baby us, we should stay with Wayne."

"Baby us?"

"Fuck him." Paulie sat down and texted Luke the news.

"I wish we could still do something with the truck," I said.

"You know anyone who's not home?"

"Yeah, right?"

I gave Paulie my cut to pay for the truck rental — it wasn't a lot, but they really nicked you with fees and insurance and a bunch of costs that aren't listed on the advertisements and the total ends up being three times what the thieves advertise for a day's rental. On top of that, we lost a day's pay.

According to Paulie, Onice said that the job was only postponed, anyway, until the next weekend. It would have been nice to say that I was busy, or if we could say "fuck him" and go out on our own, but we were already doing that on one level and, in our fight for independence, we were tied to Onice for the time being.

I believe I said this before, but we all just wanted a certain amount of security, a safety net beneath us, and this had proven an impossibility working at the company where we were comfortable with our heads just above water, month after month. Who wants to strike out for unlighted territories when they're already comfortable?

People settle for what they have — they give up and stay with a schmuck job because they believe there's a degree of safety, of certainty, and they take it out on whoever is nearest. The idea being that any change is bad. There's always the chance, so we hold onto the lousy job in case the next one is worse.

Usually the proof exists that things can get worse. It's the people without safety nets who get considered losers by the world precisely because they have no money, no prospects, no options. How far that safety net is rigged from ground zero is what determines how and when a person gives up. If you're certain where you will land, it's easier to quit.

I read once in some sporting magazine where Floyd Patterson wrote — or, more likely, had someone else write — about getting knocked out. I don't remember if he was talking about Cassius or Sonny Liston, but he said going down was almost a gratifying feeling, a relief when that punch, one he knew he wouldn't see, finally came. He knew it was coming eventually; he was going to lose.

You can brace yourself for the punches you can see, but the ones that just explode at the side of your head, those are the ones that knock you cold. When he caught one of those, completely unprepared, Patterson said that the darkness crept up from his knees to his forehead, his legs dissolved and he felt nothing but peace. He enjoyed the quiet enveloping him. The lights went down. No more fighting, no more struggling. All conflict and worry were gone for a brief few moments. As he described it, he saw his family and friends sitting ringside and he wanted to crawl over and tell them that everything would be okay; he wanted to climb through the ropes and kiss people, telling them all would be fine now. Patterson said he always awoke with a greater love for humanity after getting knocked out.

Basically, he got to commit a little bit of suicide every once in a while and woke up feeling better, believing he was among the people who cared for him and he had lost nothing but his title — the fight was over.

I understand wanting that. But, unfortunately, to achieve that peace, you have to first become heavyweight champ of something. Quitting for most people was just an acceptance of failure — of a dead end with nothing to look forward to except a paycheck and maybe the unstable peace of believing your lot in life is good enough.

© 2013 Zak Mucha. All rights reserved.

| VACHSS BIO WRITINGS ARTICLES INTERVIEWS FAQ UPDATES |

| MISSION FREE DOWNLOADS GALLERY DOGS INSIDERS RESOURCES |

Search The Zero || Site Map || Technical Help || Linkage || Contact The Zero || Main Page

The Zero © 1996 - Andrew Vachss. All rights reserved.

How to Cite Articles and Other Material from The Zero

The URL for this page is: