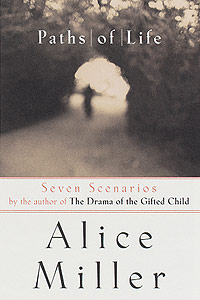

An excerpt from

Paths of Life: Seven Scenarios

by Alice Miller

Introduction

Introduction

Most people are born into a family. This family will mark them for life. Critical as young people may be of their parents, sometimes to the extent of breaking with them altogether, there is no way of escaping the more or less indelible imprint that these first family influences leave. Awareness of this fact becomes inescapable when we have children of our own.

Many people give the matter little thought. They simply put their own children through the same things they experienced themselves when they were young, and they feel they are quite right to do so. But one day they find to their amazement and dismay that it is precisely with their children and spouses or companions that they have the toughest time achieving the inner freedom they have been striving for since their youth. They are then quite likely to feel that they have reached an impasse. As they found no way out of that impasse when they were children, they had no alternative but to knuckle under, to grin and bear it. And for some adults it seems to be just the same.

But it is not. For however much we may be the product of family background, of heredity, of upbringing (for better or for worse), as adults we can gradually learn to recognize these influences. Then we are no longer under the compulsion to behave like robots. The greater our awareness of the way we have been conditioned, the more likely we are to free ourselves from our entrapments and be receptive to new information.

The reader will become acquainted with a number of personal stories in the following pages. One of the things they are designed to illustrate is that the traces left by our childhood accompany us not only in the families of our own we have as adults, they manifest themselves in the very fabric of human society, all the way up to those outsize personalities who (again, for better or for worse) have left their imprint on the course of history. In my closing reflections, I turn to the question of whether and how we can learn to gain a clearer understanding of the way hatred evolves and thus prevent it from taking root.

As every life is unique, people naturally differ in the way they integrate their childhood into their adult lives. But regardless of the way individuals may decide to go, sensitivity to the harm done by a cruel childhood is increasing and that can only be a boon for society as a whole. Child abuse in all its forms has always been with us and it is still widespread today. But only recently have the victims started realizing what has been done to them and talking to other people about it Subjects rarely touched on before are moving into the foreground of discussion, a discussion which opens up new perspectives of greater fulfillment in life for very many people.

This was brought home to me forcibly by a book I read recently. In it, fourteen fathers serving prison sentences for sexual abuse of their children and taking part in a carefully structured group therapy designed during their term of imprisonment tell the story of their crimes. It is encouraging to see how the mentalities of these men changed after they were given the opportunity to talk about what they had been through and thus felt understood and accepted. As was to be expected, they out exception stories of horrible depredations in childhood, scenarios full of sexual exploitation masquerading as a substitute for the love they were denied.

When I say encouraging, I am referring to the transformation undergone by these men on the basis of the counseling and guidance they were given. They had lived thirty, forty, fifty years without ever being given the opportunity to scrutinize and investigate what they had been through as children, much less identify it as a wrong that had been done to them. Compulsively and without qualms, they inflicted the same suffering on their own children as they had been subjected to themselves. As long as they had no grasp of the way these things relate d to each other, they were unable to free themselves from that compulsion. Only now are they ready and willing to acknowledge their ability, because they no longer regard what happened to them in their early youth as just the way things happen to be but have learned to see it as an outrageous wrong inflicted on them. Armed with this knowledge they can now mourn that horrible, twisted mess in their early lives where their childhood should have been.

This apprenticeship in critical thinking has not driven them into self-pity. Quite the contrary. From their own sufferings they have learned to empathize with their children and to acknowledge that they have harmed them for the rest of their lives. They are doing their best to repair that damage, but they know that much of it is irreversible. Not all of them have already succeeded in freeing themselves from this impasse. Some still have a long and difficult process ahead of them.

The figures in this book are my own inventions. In the course of time, however, they developed a life and a set of dynamics of their own, which in its turn enabled me to expand on what I had learned over the last few years and give it a more graphic form. The persons described here are not intended as ideals to be emulated. They simply recount what has happened to them and how they have either succeeded or failed in coming to terms with it. In describing their destinies and their environments, I consciously decided to keep outward detail to a minimum and to concentrate on the relations between the figures, on their feelings and thoughts.

There is no ready-made recipe for handling life. The objectives we have and the capacity for realizing them vary from person to person. Even though we are not always able to live up to our potential in childhood, and though the traces of earlier fears, uncertainties, and deprivations stay with us in our later lives, there is still much that we can do to change things for the better because our awareness has become more acute. This new awareness is frequently a result of encounters with feeling individuals who have been lucky enough to grow up surrounded by love and respect, who have had a less troubled childhood, who could freely experience pleasures and joys and have thus been able to lead easier, happier lives.

The figures most closely matching that description in my stories are probably Daniel, Michelle, Margot, Louise, perhaps even Gloria. They are able to listen, to identify with others; they are outgoing, concerned, and usually less prone to illusions than the figures we see them encountering. As they have experienced honesty and unconditional affection in their early years, they are better able to cope with their lives than those who are fed on illusions and later have to fight to find out the truth about themselves, like Claudia, Sandra, Anika, Helga, or Lilka.

The informal, associative style of the book should not blind the reader to the fact that my intentions in writing it go beyond the issues involved in the individual biographies of these fictitious characters and seek to pose a number of more universal questions, most notably: How do early experiences of suffering and love affect people's later lives and the way they relate to others? There are modern branches of research into areas that would be part and parcel of any attempt to answer that question, for example, observations of life in the uterus, study of newborn babies and infants, the early lives of political dictators, statistics on genocide, and so forth. But as far as I know, research has yet to be done into the way the data already collected relate to the childhood experiences of the people actively involved. These stories and reflections are designed to provide a stimulus for organized inquiries in that direction.

© Alice Miller

Check out Alice Miller's website at http://www.naturalchild.com/alice_miller/index.html.